|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

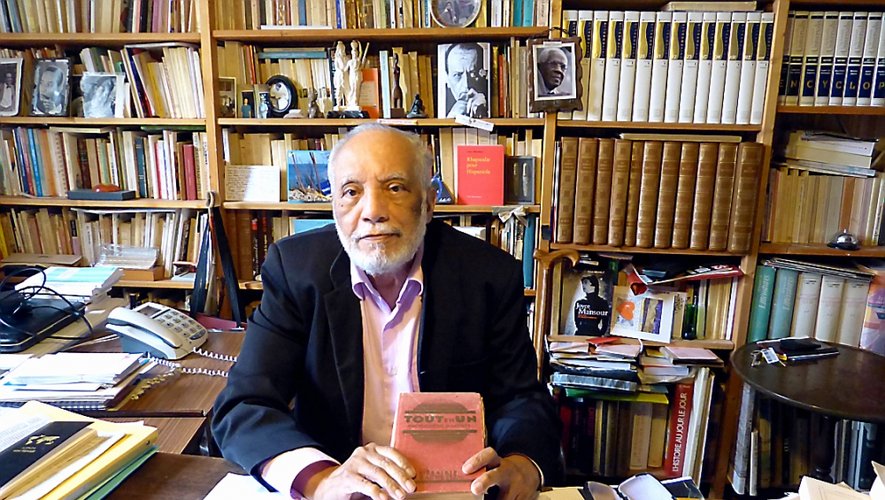

Jean Jonassaint

Keeping all our irons in the fire!

In the last century, thinking of a Haitian translation of L’Espace haïtien by the late Georges Anglade (1974), an economist friend asked me what could be the cost to switch to Creole in Haiti (i. e. as a dominant if not an exclusive usage of the popular Haitian language in all spheres of activity)? Decades later, another friend, a linguist, asked me what we would have to lose if French was no longer used in Haiti (in other words: if our educated fellows no longer mastered French)?

The answers to these two questions are urgent, but one in particular, the second, seems to me today the most imperative. I answer it as follows: in addition to a risk of isolation (our vernacular being limited to our tiny space), we would forever lose a good part of our collective memory, of our cultural heritage, of our singular contribution to common humanity. Indeed, long before Independence, the texts that shape our national history were written almost exclusively in French. Among others, I am thinking of the “journal of the Indigenous Army” of which, to the best of my knowledge, we have no explicit or close trace, apart from that left in the first work published in Haiti, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire d’Hayti (Memoirs to serve for the History of Haiti) by Boisrond-Tonnerre (1804). It is also the language of Toussaint Louverture’s correspondence, of all our constitutions, not to mention our collections of laws and regulations, Dessalines’ ordinances and of course his Proclamation in Gonaïves on January 1, 1804, reaffirming the will of the Indigènes to defend the independence of Saint-Domingue, which that very day became Hayti, reconnecting us with our Amerindian part.

Even King Henry, so close to the Anglo-Saxon world (see his correspondence with Thomas Clarkson), who, it seems, allowed himself to be sung or had “God Save the King” sung during major state ceremonies — see: Jean Comhaire, “A Royal Birthday In Haiti (15th August, 1816)”—, chooses French for his Code Henry (1812). It is also in French that one hundred years after independence, the novelist Justin Lhérisson chose to write the national anthem, La Dessalinienne.

I understand that today, some Haitians or descendants of Haitians, already cut off from our cultural heritage, would like to divorce with the French language, forgetting that we Haitians have transformed it positively by introducing new meanings to terms like independence, colonization, colonial… Thus, up to a certain point, it is also ours.

And other compatriots, just as in good faith, claim: we can translate! Yes, we can translate, but at what cost? Moreover, do we have the human and financial resources to translate even the 10th of our print production (books, brochures, articles, etc.) for more than two centuries?

Worse, “traduttore, traditore” (translating is always betraying), say the Italians — therefore, loss. Are we ready to throw away all this heritage, to assume this loss of national memory? No! Let’s enjoy our proverbs or Maurice Sixto’s lodyans as well as the poetry of Magloire-Saint Aude, the novels of Marie Chauvet or Makenzy Orcel, the works of Pradel Pompilus and Yolaine Parisot… Let’s keep all our irons in the fire!…

Indeed, even in the case of our writers who have written or write in the Haitian language like Oswald Durand, Georges Sylvain, Frankétienne, Georges Castera, Evelyne Trouillot, Maximilien Laroche, Marie-Célie Agnant, the most important part of their work is in French. The same is true of our main periodicals: Le Nouvelliste, Le Matin, Le Moniteur, Le Petit Samedi Soir, Conjonction, etc.

All this to remind us that even if our ancestors were born in Africa or elsewhere, Haitians we are, at one level or another, rooted in revolutionary France or not, a France that we mimic too often without even realizing it. Consider for example those evenings when we open our storytelling with the expression “Cric? Crac?” the very formula that we find in the oral tradition of Southern France, as Suzanne Comhaire-Sylvain already reminded us in 1937 in Les Contes haïtiens 1ère partie. Maman d’leau : origine immédiate et extension en Amérique, Afrique et Europe occidentale (p. 76). The same is true of our national motto which is a replica of a slogan of the French Revolution.

This is why, at least in part, at the opening of this publication, under the heading “Les Bonnes pages,” (for a Digital Haitian Library), I would like to draw attention to the founding text of the nation: the Proclamation of Dessalines in Gonaives on January 1, 1804, where already the main features of our literature are emerging: our Haitian French, our tragedy, our nationalist rhetoric…

And the Chief General of the Indigenous Army in this speech even seems to announce our current destiny when he proclaims: “(…) and if you ever refused or received by murmuring the laws that the genius who cares for your destinies will dictate to me for your happiness, you would deserve the fate of ungrateful peoples.”

Bonne lecture!

If you have any comments or suggestions, do not hesitate to write to us. In advance, thank you very much.