|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

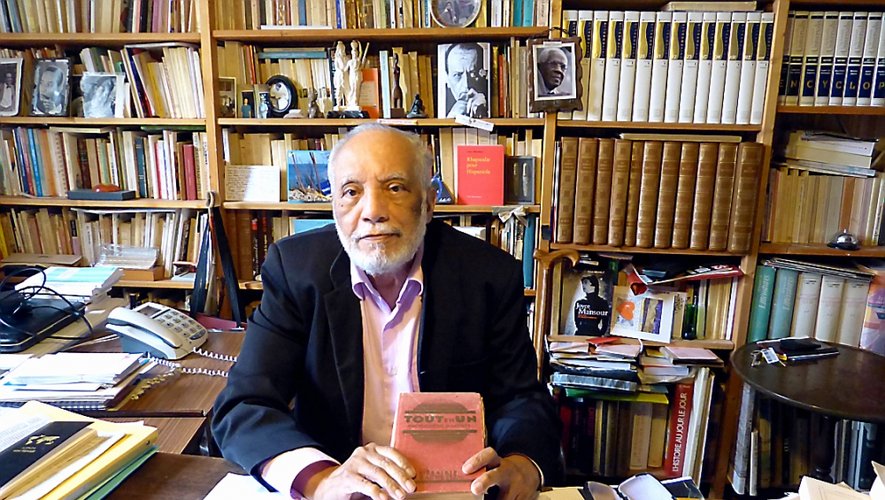

René Depestre

The Enchantment of a Rainy Hour

René Depestre, “L’enchantement d’une heure de pluie,” in Alléluia pour une femme-jardin (Paris, Gallimard © 1981), pp.131-136. Translated from the French by Asselin Charles.

Ever since she arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Ilona Kossuth had been spending most of her evenings with Margareta and me. We went together to the movies, to restaurants, to cabarets, and to football games. We rarely watched television. On those evenings we stayed home in the Ipanema apartment, we passed the time chatting. To tell the truth, on those occasions the conversation was between the two women. Ilona spoke two languages unfamiliar to me—Swedish and Hungarian. Her parents, who were from Budapest, had emigrated to Sweden before the Second World War. Margareta’s French parents were of Swedish ancestry.

Whenever the conversation might be of some interest to me, Margareta would translate Ilona’s words. She did so every time they talked about Brazil. How could one not talk about Brazil in Rio de Janeiro? Perhaps more than any of us, Ilona was under the spell of Rio. Everything in the city fascinated her to tears. The names of the neighborhoods poured forth from her mouth with a fragrance of fresh fruits: Flamengo, Gloria, Catete, Botafogo, Laranjeiras, Copacabana, Ipanema, Morro de Viuva, Leblon, Santa Teresa. Her fascination was such that it transformed the anthill of Cinelandia and the ardent affluence of Rio Branco Avenue into cool refreshing springs. Ilona deemed the patrician and racist Brazil of the upscale neighborhoods as vitally African as the Brazil of the fabulous common folk of the favelas and suburbs.

We would pause in the gardens of Rio, breathless before the exuberance of the vegetation. In the Caribbean I had never beheld shades of green that are in such sensual harmony with the jade of the sea. With Ilona and Margareta, I also discovered that plants with the heaviest foliage could rise up to the highest fantasy.

That year, Santa Teresa was still a haven of bougainvilleas, palm trees, banana trees, balustraded verandahs, cool shades, and azulejos that were like balconies overlooking the world’s innocence. The one thing that irritated Ilona and Margareta about the fête that was Rio was the endless undulation of the city around Guanabara Bay. This geometry of concealed buttocks and secret bellies was undoubtedly the model of paradise for the Brazilian machos. “To dream in a city where God is so much in love with curves,” my two friends would say, “one should escape from its visceral cycloids and rise up to Pão de Açúcar, Morro Dois Irmãos, Corcovado, Serra dos Órgãos, Gavea.” “At sea level one can only enjoy, but one cannot dream,” they decreed peremptorily.

Margareta translated my response:

“You’re saying that because you’ve just arrived here. You haven’t yet lived a Rio carnaval. When the Brazilian imagination erupts, at sea level Rio invents dreams with its feet, with its hips, with its guts, with its illuminated head.”

My two European women, both equally beautiful, felt too “ill squared” amidst the feminine curves that gave a round shape to living spaces everywhere in Brazil. They were still perplexed when I told them, without flattery, that the graceful curves of their bodies on the Copacabana beach could make one as dizzy as the perpetually moving mystery of the Brazilian woman.

What makes the Carioca sail so distinctly like a vessel amidst the rolling waves, the thing that makes other women look like sleepy logs beside her, is that her beauty always moves to nature’s rhythm. Standing or sitting, walking or making love, she never misses a beat. The lyrical cadence of her presence in the world has nothing to do with her having magnificently full breasts and a bountiful behind. You too have those marvelous attributes. What is it that you lack? You have been taught since childhood that it is wrong to abandon yourself to the rhythm of the night, of the trees, of the wind, of the waters of the earth and the sky. Yet, that rhythm is in you; it is the lyrical song of your very blood.

One Saturday afternoon, sometime after that conversation, Margareta and I were at home pottering about. We had to assemble a set of shelves for some hundred new books. We listened to Mozart concertos while we worked. Someone rang the doorbell; it was Ilona. She had come to help us. She came directly from the beach. Her twenty years exuded the smell of warm salt and the scent of some animal from the Hungarian woods or the Swedish forests. Her naturally blue eyes mirrored the Rio sky. Her presence blended beautifully with the refreshing notes of Mozart.

“It’s going to rain,” she said in Portuguese. “There’s a rainstorm coming from the sea.”

“Wonderful,” I replied. “This will be your first real tropical rain since you arrived here. I know what’s that like. Miracles of water rained on my childhood.”

The first drops tinkled on the glass of the living room’s bay window. Then, all of a sudden the sky burst open over Ipanema. We couldn’t see anything outside anymore, only a sheet of rain as tightly woven as a boat’s sail. A pleasant twilight fell over the living room. Ilona’s and Margareta’s hair glimmered like hurricane lamps.

Ilona was standing at the bay window, rendered speechless and breathless by the raging torrential afternoon rain.

Ilona suddenly took off her blouse and her bra. Her breasts swayed to the rhythm of the rain. Both Margarita’s and my hands shook as we continued to arrange the books on the shelves. Then, in a sort of blessed trance, Ilona let her skirt and her slip fall to floor. She was the most beautiful Brazilian woman the Rio de Janeiro rain could ever fashion. A marvelous current flowed from Ilona to Margareta. My wife in turn removed her clothes and walked over to stand by her friend. Their lives were now vibrating to the cadence of the Brazilian season.

I was mad with desire and joy. I was a son the Caribbean, a man of the Brazilian depths, not some cloven-hoofed, horned Dionysos leading these “white goddesses” on the path of joy. Carried by the very rhythm of their blood, Ilona and Margareta were being initiated into the mystery of our American lands.

I undressed and joined them at the window. I suddenly rediscovered the spirit of my childhood. The sweet sounds of Mozart drifted from afar and blended with the water to dazzle our lives. I travelled madly with Ilona on the living room carpet while carrying Margareta’s equally wild curves on my back. There will never be anything like that ineffable rainy afternoon.